A mild excursus into the banality of evil, or at least of evil deeds unmotivated by fanaticism, perversion or sociopathy. It lacks smut, bad language, exciting sex scenes or gratuitous violence. Instead, this play relies heavily on a good deal of discussion about the killing or not, will we, won't we, of Inès de Castro, secret wife of Pedro, the young Prince of Portugal by his father. Lacking any of the conventional plot gambits which would have made this a successful film, play, or book, the King decides eventually to kill her. He does this more out of boredom than anything else. Its like a Waiting for Godot but with Vlad and Est having someone else other than themselves to hang. The digging up, crowing and veneration of the corpse (the high points for which the story is justly well known outside the English-speaking world) all fall outside the scope of the drama. Sadly.

ACTE III - SCÈNE VI (Ctd...)

L'OMBRE DE L'INFANTE

ACTE III - SCÈNE VI (Ctd...)

L'OMBRE DE L'INFANTE

- Quelqu'un qui te veut du bien. Quitte cette salle immédiatement. N'encoute plus le Roi. Il jette en toi ses secrets désespérés, comme dans une tombe. Ensuite il rabattra sur toi la pierre de la tombe, pour que tu ne parles jamais.

INÈS

- Je ne quitterai pas celui qui m'a dit:"Je suis un roi de doleur." Alors il ne mentait pas. Et je n'ai pas peur de lui.

The shadow of the then Infante of Spain calls over to, then implores, Inès de Castro to immediately quit the room where Inès has been conversing with the rapidly degenerating Ferrante, King of Portugal who also happens to be father to Pedro the Prince and heir who has previously and in secret married Inès against the wishes of the King, his father. On his attempt to contrive a political marriage between Inès and the Infante, the prior marriage between Pedro and Inès is made public to the King.

The Infante is indifferent to Pedro, who is banished to one of his father's castles while Inès remains free for the time being. The King's councillors suggest that unless the prior marriage can be annulled by the unwilling Pope, (who does not in any case favour Ferrante) banishment is insufficient to silence Inès. The King also fears that on his death Inès, if still living, will assume the title of Queen of Portugal at Pedro's side. The King wavers back and forth, debating the murder. The Infante hears from a noble waiting-man of the King's chamber, the plan to kill Inès, and in a lengthy scene at the gate of the castle wherein Pedro is held, she warns Inès of her likely fate. Disbelieving, justifying, explaining things to herself, Inès finds herself back in the company of the King and of the councillors whose council is that she die. And at this juncture, from the next to penultimate scene of the play, is taken our excerpt: the Infante's final hushed warning as it has become apparent to the departing Spanish Ladies that the King is indeed set on the course of action which was previously overheard at the council chamber door.

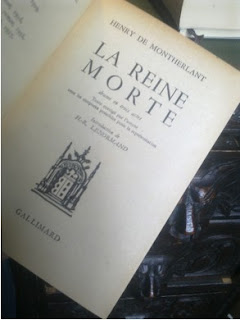

Written in 1942, this slender volume claims for Montherlant's play that 'elle fut le plus grand succès théâtral en France sous l'occupation.' It derives its title of The Dead Queen from the story, well known in Iberia, of Inès de Catsro, secret and much loved wife of Pedro I of Portugal, who was murdered by his father but exhumed later by Pedro who then crowned the cadaver of Inès as Queen to be adored and accepted by the nobility of Portugal. The elaborately gothic coffins of Inès and Pedro lie in the north and south trancepts of the Abbey of Alcobaça, just to the noth of Lisbon. Though defaced and knocked around, restored and reassembled, the white marble coffins are place such that on the day of judgement, the two lovers will rise up facing one another, the first thing that each of them will see. On one of the coffins is the inscription 'Ate ao fin de Mundo' - until the ending of the world, when hopefully they shall meet again.

The story of the crowning of the coronation of the dead queen, the tracking down of her murderers by Pedro (they are represented in stone supporting one of the huge coffins) and of the secret love affair date historically from the fourteenth century and differ in many details from the relations described in the play. The verses from 1572 known in Portuguese as Os Lusíadas by Luís de Camões (and in a Penguin translation) touch on the story of Inès and Pedro, as do several other fictional works (Inès de Castro (1826) by M. de Genlis), and including plays and a 1996 opera Inès de Castro by James MacMillan. As ever, a Wikipedia version of the story exists which I have no interest in repeating, but is there for handy reference for those who care. In this play, it is sufficient to note that Montherlant plays fast and loose with historical characters and events but not in any way which detracts from his theme, or the basic historic basis which is no less reasonable than the portrayal of Elizabeth I in Scott's Kennilworth or of Richard III from Shakespeare. The basic plot is there. Pedro marries the wrong girl. His father kills her. On the father's death, Pedro digs her up and crowns her Queen. End of Love Story. Its like Romeo and Julliet but without the humorous cut and thrust of the first two acts. Two youngsters (except they're both 26 in this play) dreadfully in love, much thwarted. Tragic, yet strangely sustaining in the Até Ao fin de Mondo-ness of it all. Its not Shakespeare. But if it is, then its not the good bits of Shakespeare. So shaken as we are, so wan with care, the old King is not. Miffed and bored yes. Eloquent with it, no.

Considering the period in which it was written, I had expected a nuanced play, suggesting a language of resistance, perhaps reminiscent in some way of Jean Anouilh's (1943) Antigone, in which the parallels between occupied and occupiers were not indiscernible; or of the contemporary Chinese film-maker Yimou Zhang (House of Flying Daggers (2004), etc) whose films are accepted as orthodox in China despite their underlying controversial message that the individual cannot win against the state. Inès is offerred several ways out of the situation. She speaks at length with an initially not unsympathetic though ill King. The councillors have a bland and unsubtle policy agenda in which logically, if the strategic ends of Portugal are predicated on the marriage of Pedro and the Infante, then either he must marry her by choice (which he will not and cannot), after an annulation of the marriage by the (uncooperative) Pope, or he must marry her by compulsion following the murder of Inès, who in exile would otherwise form a rallying point for anti-Portuguese dissent. When it becomes clear that the Infante is having non of it, packing her bags and heading home, it would seem that the King's persistence is more from boredom with the situation as much as anything else. And he says as much in Acte III Scène IV:

- Oh! Je suis fatigué de cette situation. Je voudrais qu'elle prît une autre forme....et je suis fatigué de vous, de votre existence. Fatigué de vous vouloir du bien, fatigué de vouloir vous sauver. Ah! Pourquoi existez-vous?

The king, delineates his raisons ignobles, and returns time and again to the very tedium of trying to sort out and save the situation from the vying suggestions and predilections, policies and prejudices of the court, which seem to make the action of these characters wallow in a glue or treacle that creates the slow-motion dreamscape of failing to running away from a pursuing fast overtaking terror. It is tiredness and indifference which take Inès to her death rather than political ambition, intrigue, vengeance or jealousy. The banality of the decision to kill her. The grinding boredom of have to finish her off. Get it over and done with. It is this which has contemporary resonance with some of our contemporary concern with disappearing people (i.e. the verb 'to disappear' a person, by contrast with a person who becomes invisible) and rendition. Inès has done nothing which the King can find deserving of punishment at all. When he hears of the situation, he says that Inès should be free, that the situation can be resolved. But as it grinds on, the King merely becomes bred with the inconvenient Inès who is, in modern terminology, disappeared. Pedro, obviously reappears her, as sometime we some of our national citizens reappearing, mainly in the press, recounting their treatment at the hands of the American in Guantanamo. They at least are not actual cadavers. In fiction, Orwell's Winston Smith returns from his interrogation changed, and in Stalinist Russia, some victims survived in 'retirement' in Dachas where though alive, they could do no harm, or lingered like a Speer and a Hess in Spandau long after their self-deemed peaks had passed ignobly into the past. Inès returns, but without victory and without celebration, and though crowned and accounted a queen of Portugal, this is surely one of the the most hollow of victories.

There was an English translation of this, but after reading the original text, my temptation to dabble with the translator's art is low-to-middling at best. Non existent wouldn't be far from the truth. Nonetheless, if the banality of evil is your thing (and clearly from the number of films and books about the Nazis, the Bulger killing etc etc is anything to go by), then La Reine Morte should excite and titillate. Presumably, it is available from abebooks.

The shadow of the then Infante of Spain calls over to, then implores, Inès de Castro to immediately quit the room where Inès has been conversing with the rapidly degenerating Ferrante, King of Portugal who also happens to be father to Pedro the Prince and heir who has previously and in secret married Inès against the wishes of the King, his father. On his attempt to contrive a political marriage between Inès and the Infante, the prior marriage between Pedro and Inès is made public to the King.

The Infante is indifferent to Pedro, who is banished to one of his father's castles while Inès remains free for the time being. The King's councillors suggest that unless the prior marriage can be annulled by the unwilling Pope, (who does not in any case favour Ferrante) banishment is insufficient to silence Inès. The King also fears that on his death Inès, if still living, will assume the title of Queen of Portugal at Pedro's side. The King wavers back and forth, debating the murder. The Infante hears from a noble waiting-man of the King's chamber, the plan to kill Inès, and in a lengthy scene at the gate of the castle wherein Pedro is held, she warns Inès of her likely fate. Disbelieving, justifying, explaining things to herself, Inès finds herself back in the company of the King and of the councillors whose council is that she die. And at this juncture, from the next to penultimate scene of the play, is taken our excerpt: the Infante's final hushed warning as it has become apparent to the departing Spanish Ladies that the King is indeed set on the course of action which was previously overheard at the council chamber door.

Written in 1942, this slender volume claims for Montherlant's play that 'elle fut le plus grand succès théâtral en France sous l'occupation.' It derives its title of The Dead Queen from the story, well known in Iberia, of Inès de Catsro, secret and much loved wife of Pedro I of Portugal, who was murdered by his father but exhumed later by Pedro who then crowned the cadaver of Inès as Queen to be adored and accepted by the nobility of Portugal. The elaborately gothic coffins of Inès and Pedro lie in the north and south trancepts of the Abbey of Alcobaça, just to the noth of Lisbon. Though defaced and knocked around, restored and reassembled, the white marble coffins are place such that on the day of judgement, the two lovers will rise up facing one another, the first thing that each of them will see. On one of the coffins is the inscription 'Ate ao fin de Mundo' - until the ending of the world, when hopefully they shall meet again.

The story of the crowning of the coronation of the dead queen, the tracking down of her murderers by Pedro (they are represented in stone supporting one of the huge coffins) and of the secret love affair date historically from the fourteenth century and differ in many details from the relations described in the play. The verses from 1572 known in Portuguese as Os Lusíadas by Luís de Camões (and in a Penguin translation) touch on the story of Inès and Pedro, as do several other fictional works (Inès de Castro (1826) by M. de Genlis), and including plays and a 1996 opera Inès de Castro by James MacMillan. As ever, a Wikipedia version of the story exists which I have no interest in repeating, but is there for handy reference for those who care. In this play, it is sufficient to note that Montherlant plays fast and loose with historical characters and events but not in any way which detracts from his theme, or the basic historic basis which is no less reasonable than the portrayal of Elizabeth I in Scott's Kennilworth or of Richard III from Shakespeare. The basic plot is there. Pedro marries the wrong girl. His father kills her. On the father's death, Pedro digs her up and crowns her Queen. End of Love Story. Its like Romeo and Julliet but without the humorous cut and thrust of the first two acts. Two youngsters (except they're both 26 in this play) dreadfully in love, much thwarted. Tragic, yet strangely sustaining in the Até Ao fin de Mondo-ness of it all. Its not Shakespeare. But if it is, then its not the good bits of Shakespeare. So shaken as we are, so wan with care, the old King is not. Miffed and bored yes. Eloquent with it, no.

Considering the period in which it was written, I had expected a nuanced play, suggesting a language of resistance, perhaps reminiscent in some way of Jean Anouilh's (1943) Antigone, in which the parallels between occupied and occupiers were not indiscernible; or of the contemporary Chinese film-maker Yimou Zhang (House of Flying Daggers (2004), etc) whose films are accepted as orthodox in China despite their underlying controversial message that the individual cannot win against the state. Inès is offerred several ways out of the situation. She speaks at length with an initially not unsympathetic though ill King. The councillors have a bland and unsubtle policy agenda in which logically, if the strategic ends of Portugal are predicated on the marriage of Pedro and the Infante, then either he must marry her by choice (which he will not and cannot), after an annulation of the marriage by the (uncooperative) Pope, or he must marry her by compulsion following the murder of Inès, who in exile would otherwise form a rallying point for anti-Portuguese dissent. When it becomes clear that the Infante is having non of it, packing her bags and heading home, it would seem that the King's persistence is more from boredom with the situation as much as anything else. And he says as much in Acte III Scène IV:

- Oh! Je suis fatigué de cette situation. Je voudrais qu'elle prît une autre forme....et je suis fatigué de vous, de votre existence. Fatigué de vous vouloir du bien, fatigué de vouloir vous sauver. Ah! Pourquoi existez-vous?

The king, delineates his raisons ignobles, and returns time and again to the very tedium of trying to sort out and save the situation from the vying suggestions and predilections, policies and prejudices of the court, which seem to make the action of these characters wallow in a glue or treacle that creates the slow-motion dreamscape of failing to running away from a pursuing fast overtaking terror. It is tiredness and indifference which take Inès to her death rather than political ambition, intrigue, vengeance or jealousy. The banality of the decision to kill her. The grinding boredom of have to finish her off. Get it over and done with. It is this which has contemporary resonance with some of our contemporary concern with disappearing people (i.e. the verb 'to disappear' a person, by contrast with a person who becomes invisible) and rendition. Inès has done nothing which the King can find deserving of punishment at all. When he hears of the situation, he says that Inès should be free, that the situation can be resolved. But as it grinds on, the King merely becomes bred with the inconvenient Inès who is, in modern terminology, disappeared. Pedro, obviously reappears her, as sometime we some of our national citizens reappearing, mainly in the press, recounting their treatment at the hands of the American in Guantanamo. They at least are not actual cadavers. In fiction, Orwell's Winston Smith returns from his interrogation changed, and in Stalinist Russia, some victims survived in 'retirement' in Dachas where though alive, they could do no harm, or lingered like a Speer and a Hess in Spandau long after their self-deemed peaks had passed ignobly into the past. Inès returns, but without victory and without celebration, and though crowned and accounted a queen of Portugal, this is surely one of the the most hollow of victories.

There was an English translation of this, but after reading the original text, my temptation to dabble with the translator's art is low-to-middling at best. Non existent wouldn't be far from the truth. Nonetheless, if the banality of evil is your thing (and clearly from the number of films and books about the Nazis, the Bulger killing etc etc is anything to go by), then La Reine Morte should excite and titillate. Presumably, it is available from abebooks.