Christopher Isherwood (1945): Goodbye to Berlin. (1975 Folio Society edition with drawings by George Grosz) pp 256.

Saturday 9 October 2010

Wednesday 22 September 2010

Monday 23 August 2010

New Books: to be reviewed

Ivan D. Illich (1971) Deschooling Society. Caldar and Boyars, London, 116 pages.

T.C. Lethbridge (1961) Ghost and Ghoul. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 153 pages.

Two books from the shelves, linked only by the trajectory of development away from mainstream academia by two authors who become progressively less able to accept the received wisdom of their respective disciplines as they develop their thought. The topics and methods they chose are widely different, but the process by which they question what seems common sense, provides the interest to me.

Tom Lethbridge critiques the accepted wisdom of scientific methods and Ivan Illich urges a radical re-examination of social myths and the institutions which increasingly govern our lives. Illich writes Deschooling Society in 1971, Lethbridge Ghost and Ghoul in 1961. I have already tinkered about at the edge of Tom Lethbridge via references in Tom Graves and from themes brought up in T.J. Hudson's Phychic Phenomena of 1893. Illich is more serious, and more pertinent. With the A Level and GCSE results just out, the newspapers full of inflationary grade accusations, and fears that 99% of everyone might not get to university irrespective of talent cost or interest, it seems timely to go back to the late 1960s to read from Illich WHY WE MUST ABOLISH SCHOOLING (I quote from the dustjacket). I will read and comment on both books over the next couple of weeks.

Please do join me if you have access to either of these.

Labels:

Ivan Illich,

T.C. Lethbridge

"The War with Hannibal" Livy translated by Aubrey de Selincourt

Livy (59 B.C. - 17 A.D.): Limited to the amount of weight I could take by opting only to take hand luggage on a recent flight to Romania, I found myself in the difficult position of selecting a single book to take with me for a month abroad (hence the paucity of recent posts). In similar circumstances during fieldwork trips to Papua New Guinea, I have usually in the past opted for Dickens-like products: a little Dorritt, goes a long way. I have spun Bleak House out for entire months in the jungle without the need for alternative sustenance. But in recent years, I have reverted to an earlier practice of taking away a Penguin Classics translation of something or other. The Quintus Curtius Rufus History of Alexander came to Romania with me last year along with Xenophon's Persian Expedition; and before that, Hellenica came to Lycia walking at the suggestion of Freya Stark in her (1956) Lycian Shore, which was part of my pre-reading for the trek through the mountains sketching the rock tombs a la Charles Fellows. That trip set me off on a revisit to the classical references to Alexander, and by habit alone, it has come to seem appropriate to have a battered Penguin Classics in the rucksack rather than something more Dickensian or George Elliotsy.

Livy has not stinted in volume here. The account of the war with Hannibal is written in an annual format, in which he deals with the events of the year rather than an integrated structural explanation of each set of conflicts as it develops. This style cuts up the narrative as he skips back and forth between the number of concurrent actions which make up the second Punic War between Rome and Carthage between 219 and 201 B.C. That said, this is a fantastic battle of personalities: the speeches and actions main protagonists are well developed and the detail is often exquisite even if the historical accuracy might be doubted:

"...the dismounted cavalry fought on in the full knowledge of of defeat; they made no attempt to escape, preferring to die where they stood; and their refusal to budge, by delaying total victory even for a moment, further incensed the triumphant enemy, who unable to drive them from their ground, mercilessly cut them down. Some few survivors did indeed turn and run, wounded and worn out though they were."

This describing the calamitous Roman defeat in 216 B.C. at Cannae as the wounded consul Paullus sits on his stone bleeding profusely and about to fall under a shower of spears "his killers not even knowing whom they killed." Livy leads us quickly from the siege of Saguntum, then over the Alps with Hannibal into Italy from Spain to the Roman defeats at Cannae, the destruction of the Roman army at Boii, Marcellus's victory at Syracuse and the death of Archimedes in his garden. We pass the Volturnus, the capture and destruction of Capua, the collapse of Carthaginian efforts in Spain, and on to the final defeat of Hannibal, which no matter how often I read it always seems a shame. I'm never sure that the good guys win this one. If you don't know the story, and have a lot of time in airports, bus stations or in tents-in-the-rain to fill up, then I would recommend taking a copy of Hannibal with you. To be honest, I also took on the plane a slim modern copy of RLS's most excellent "Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes" because it covered a similar traverse as Hannibal. RLS is very enjoyable but not of sufficient length. I wouldn't quite cal him chick lit, but it is light, frothy and quick to read. He filled in a very enjoyable evening on his Modestine, but for the remaining two weeks I fell back on Livy.

Labels:

History,

Livy,

Non-Fiction,

Penguin,

War with Hannibal

Gardens Gallery Exhibition, Cheltenham

A link to our Flagstonepress blog article on the recent exhibition in Cheltenham.

Thursday 19 August 2010

Sunday 6 June 2010

Showler, Karl (1978): The Observation Hive

One of a steadily growing collection of bee-keeping related books in my collection. I'll add a few more in coming weeks as I get to review them steadily. This particular offering is sold on the basis that its the only book dealing specifically with the observation hive. Having just procured such an item from eBay, this title from AbeBooks seemed like a good starting place to try to cover all the information I need to start up a small colony of bees using a few frames from the existing three hives in the apiary. However, as a practical "How to" type of book this leaves me slightly underimpressed. Perhaps it wasn't the aim of the author to discuss in detail how observation hives work. What he has done is to spend most of the book informing the reader what an observation hive looks like and who has used one in the past. The pertinent section for my purposes is Chapter 5: Stocking and Care of an Observation Hive (pp. 63-75). Of these twelve pages, only one or two paragraphs actually deal with actionable details. He says: "Preparing nuclei from a number of colonies may be practised as part of the main apiary swarm control system but it does add a further complication to preliminary work." What those complications might be, and how preparation of nuclei add to normal swarm control are not mentioned further. Basically, I didn't learn anything from this book that I haven't already learned from other beekeeping books or from the practise of beekeeping in the apiary. And that is not to mean that I know very much. Three seasons practice, with one or two complete failures and three hives extant is my record to date. Not much knowledge. so to read a book like this, purporting to be a specialist sub-section of beekeeping, and to learn nothing new is disappointing. Perhaps it is unfair of me to expect a technical manual when this clearly is not one, and was written at a time when technical User Manuals were still a thing of the future. In terms of utility then, I am disappointed.

Labels:

Bees,

Non-Fiction,

Showler

Monday 26 April 2010

Henry de Montherlant (1942): 'La Reine Morte'

A mild excursus into the banality of evil, or at least of evil deeds unmotivated by fanaticism, perversion or sociopathy. It lacks smut, bad language, exciting sex scenes or gratuitous violence. Instead, this play relies heavily on a good deal of discussion about the killing or not, will we, won't we, of Inès de Castro, secret wife of Pedro, the young Prince of Portugal by his father. Lacking any of the conventional plot gambits which would have made this a successful film, play, or book, the King decides eventually to kill her. He does this more out of boredom than anything else. Its like a Waiting for Godot but with Vlad and Est having someone else other than themselves to hang. The digging up, crowing and veneration of the corpse (the high points for which the story is justly well known outside the English-speaking world) all fall outside the scope of the drama. Sadly.

ACTE III - SCÈNE VI (Ctd...)

L'OMBRE DE L'INFANTE

ACTE III - SCÈNE VI (Ctd...)

L'OMBRE DE L'INFANTE

- Quelqu'un qui te veut du bien. Quitte cette salle immédiatement. N'encoute plus le Roi. Il jette en toi ses secrets désespérés, comme dans une tombe. Ensuite il rabattra sur toi la pierre de la tombe, pour que tu ne parles jamais.

INÈS

- Je ne quitterai pas celui qui m'a dit:"Je suis un roi de doleur." Alors il ne mentait pas. Et je n'ai pas peur de lui.

The shadow of the then Infante of Spain calls over to, then implores, Inès de Castro to immediately quit the room where Inès has been conversing with the rapidly degenerating Ferrante, King of Portugal who also happens to be father to Pedro the Prince and heir who has previously and in secret married Inès against the wishes of the King, his father. On his attempt to contrive a political marriage between Inès and the Infante, the prior marriage between Pedro and Inès is made public to the King.

The Infante is indifferent to Pedro, who is banished to one of his father's castles while Inès remains free for the time being. The King's councillors suggest that unless the prior marriage can be annulled by the unwilling Pope, (who does not in any case favour Ferrante) banishment is insufficient to silence Inès. The King also fears that on his death Inès, if still living, will assume the title of Queen of Portugal at Pedro's side. The King wavers back and forth, debating the murder. The Infante hears from a noble waiting-man of the King's chamber, the plan to kill Inès, and in a lengthy scene at the gate of the castle wherein Pedro is held, she warns Inès of her likely fate. Disbelieving, justifying, explaining things to herself, Inès finds herself back in the company of the King and of the councillors whose council is that she die. And at this juncture, from the next to penultimate scene of the play, is taken our excerpt: the Infante's final hushed warning as it has become apparent to the departing Spanish Ladies that the King is indeed set on the course of action which was previously overheard at the council chamber door.

Written in 1942, this slender volume claims for Montherlant's play that 'elle fut le plus grand succès théâtral en France sous l'occupation.' It derives its title of The Dead Queen from the story, well known in Iberia, of Inès de Catsro, secret and much loved wife of Pedro I of Portugal, who was murdered by his father but exhumed later by Pedro who then crowned the cadaver of Inès as Queen to be adored and accepted by the nobility of Portugal. The elaborately gothic coffins of Inès and Pedro lie in the north and south trancepts of the Abbey of Alcobaça, just to the noth of Lisbon. Though defaced and knocked around, restored and reassembled, the white marble coffins are place such that on the day of judgement, the two lovers will rise up facing one another, the first thing that each of them will see. On one of the coffins is the inscription 'Ate ao fin de Mundo' - until the ending of the world, when hopefully they shall meet again.

The story of the crowning of the coronation of the dead queen, the tracking down of her murderers by Pedro (they are represented in stone supporting one of the huge coffins) and of the secret love affair date historically from the fourteenth century and differ in many details from the relations described in the play. The verses from 1572 known in Portuguese as Os Lusíadas by Luís de Camões (and in a Penguin translation) touch on the story of Inès and Pedro, as do several other fictional works (Inès de Castro (1826) by M. de Genlis), and including plays and a 1996 opera Inès de Castro by James MacMillan. As ever, a Wikipedia version of the story exists which I have no interest in repeating, but is there for handy reference for those who care. In this play, it is sufficient to note that Montherlant plays fast and loose with historical characters and events but not in any way which detracts from his theme, or the basic historic basis which is no less reasonable than the portrayal of Elizabeth I in Scott's Kennilworth or of Richard III from Shakespeare. The basic plot is there. Pedro marries the wrong girl. His father kills her. On the father's death, Pedro digs her up and crowns her Queen. End of Love Story. Its like Romeo and Julliet but without the humorous cut and thrust of the first two acts. Two youngsters (except they're both 26 in this play) dreadfully in love, much thwarted. Tragic, yet strangely sustaining in the Até Ao fin de Mondo-ness of it all. Its not Shakespeare. But if it is, then its not the good bits of Shakespeare. So shaken as we are, so wan with care, the old King is not. Miffed and bored yes. Eloquent with it, no.

Considering the period in which it was written, I had expected a nuanced play, suggesting a language of resistance, perhaps reminiscent in some way of Jean Anouilh's (1943) Antigone, in which the parallels between occupied and occupiers were not indiscernible; or of the contemporary Chinese film-maker Yimou Zhang (House of Flying Daggers (2004), etc) whose films are accepted as orthodox in China despite their underlying controversial message that the individual cannot win against the state. Inès is offerred several ways out of the situation. She speaks at length with an initially not unsympathetic though ill King. The councillors have a bland and unsubtle policy agenda in which logically, if the strategic ends of Portugal are predicated on the marriage of Pedro and the Infante, then either he must marry her by choice (which he will not and cannot), after an annulation of the marriage by the (uncooperative) Pope, or he must marry her by compulsion following the murder of Inès, who in exile would otherwise form a rallying point for anti-Portuguese dissent. When it becomes clear that the Infante is having non of it, packing her bags and heading home, it would seem that the King's persistence is more from boredom with the situation as much as anything else. And he says as much in Acte III Scène IV:

- Oh! Je suis fatigué de cette situation. Je voudrais qu'elle prît une autre forme....et je suis fatigué de vous, de votre existence. Fatigué de vous vouloir du bien, fatigué de vouloir vous sauver. Ah! Pourquoi existez-vous?

The king, delineates his raisons ignobles, and returns time and again to the very tedium of trying to sort out and save the situation from the vying suggestions and predilections, policies and prejudices of the court, which seem to make the action of these characters wallow in a glue or treacle that creates the slow-motion dreamscape of failing to running away from a pursuing fast overtaking terror. It is tiredness and indifference which take Inès to her death rather than political ambition, intrigue, vengeance or jealousy. The banality of the decision to kill her. The grinding boredom of have to finish her off. Get it over and done with. It is this which has contemporary resonance with some of our contemporary concern with disappearing people (i.e. the verb 'to disappear' a person, by contrast with a person who becomes invisible) and rendition. Inès has done nothing which the King can find deserving of punishment at all. When he hears of the situation, he says that Inès should be free, that the situation can be resolved. But as it grinds on, the King merely becomes bred with the inconvenient Inès who is, in modern terminology, disappeared. Pedro, obviously reappears her, as sometime we some of our national citizens reappearing, mainly in the press, recounting their treatment at the hands of the American in Guantanamo. They at least are not actual cadavers. In fiction, Orwell's Winston Smith returns from his interrogation changed, and in Stalinist Russia, some victims survived in 'retirement' in Dachas where though alive, they could do no harm, or lingered like a Speer and a Hess in Spandau long after their self-deemed peaks had passed ignobly into the past. Inès returns, but without victory and without celebration, and though crowned and accounted a queen of Portugal, this is surely one of the the most hollow of victories.

There was an English translation of this, but after reading the original text, my temptation to dabble with the translator's art is low-to-middling at best. Non existent wouldn't be far from the truth. Nonetheless, if the banality of evil is your thing (and clearly from the number of films and books about the Nazis, the Bulger killing etc etc is anything to go by), then La Reine Morte should excite and titillate. Presumably, it is available from abebooks.

The shadow of the then Infante of Spain calls over to, then implores, Inès de Castro to immediately quit the room where Inès has been conversing with the rapidly degenerating Ferrante, King of Portugal who also happens to be father to Pedro the Prince and heir who has previously and in secret married Inès against the wishes of the King, his father. On his attempt to contrive a political marriage between Inès and the Infante, the prior marriage between Pedro and Inès is made public to the King.

The Infante is indifferent to Pedro, who is banished to one of his father's castles while Inès remains free for the time being. The King's councillors suggest that unless the prior marriage can be annulled by the unwilling Pope, (who does not in any case favour Ferrante) banishment is insufficient to silence Inès. The King also fears that on his death Inès, if still living, will assume the title of Queen of Portugal at Pedro's side. The King wavers back and forth, debating the murder. The Infante hears from a noble waiting-man of the King's chamber, the plan to kill Inès, and in a lengthy scene at the gate of the castle wherein Pedro is held, she warns Inès of her likely fate. Disbelieving, justifying, explaining things to herself, Inès finds herself back in the company of the King and of the councillors whose council is that she die. And at this juncture, from the next to penultimate scene of the play, is taken our excerpt: the Infante's final hushed warning as it has become apparent to the departing Spanish Ladies that the King is indeed set on the course of action which was previously overheard at the council chamber door.

Written in 1942, this slender volume claims for Montherlant's play that 'elle fut le plus grand succès théâtral en France sous l'occupation.' It derives its title of The Dead Queen from the story, well known in Iberia, of Inès de Catsro, secret and much loved wife of Pedro I of Portugal, who was murdered by his father but exhumed later by Pedro who then crowned the cadaver of Inès as Queen to be adored and accepted by the nobility of Portugal. The elaborately gothic coffins of Inès and Pedro lie in the north and south trancepts of the Abbey of Alcobaça, just to the noth of Lisbon. Though defaced and knocked around, restored and reassembled, the white marble coffins are place such that on the day of judgement, the two lovers will rise up facing one another, the first thing that each of them will see. On one of the coffins is the inscription 'Ate ao fin de Mundo' - until the ending of the world, when hopefully they shall meet again.

The story of the crowning of the coronation of the dead queen, the tracking down of her murderers by Pedro (they are represented in stone supporting one of the huge coffins) and of the secret love affair date historically from the fourteenth century and differ in many details from the relations described in the play. The verses from 1572 known in Portuguese as Os Lusíadas by Luís de Camões (and in a Penguin translation) touch on the story of Inès and Pedro, as do several other fictional works (Inès de Castro (1826) by M. de Genlis), and including plays and a 1996 opera Inès de Castro by James MacMillan. As ever, a Wikipedia version of the story exists which I have no interest in repeating, but is there for handy reference for those who care. In this play, it is sufficient to note that Montherlant plays fast and loose with historical characters and events but not in any way which detracts from his theme, or the basic historic basis which is no less reasonable than the portrayal of Elizabeth I in Scott's Kennilworth or of Richard III from Shakespeare. The basic plot is there. Pedro marries the wrong girl. His father kills her. On the father's death, Pedro digs her up and crowns her Queen. End of Love Story. Its like Romeo and Julliet but without the humorous cut and thrust of the first two acts. Two youngsters (except they're both 26 in this play) dreadfully in love, much thwarted. Tragic, yet strangely sustaining in the Até Ao fin de Mondo-ness of it all. Its not Shakespeare. But if it is, then its not the good bits of Shakespeare. So shaken as we are, so wan with care, the old King is not. Miffed and bored yes. Eloquent with it, no.

Considering the period in which it was written, I had expected a nuanced play, suggesting a language of resistance, perhaps reminiscent in some way of Jean Anouilh's (1943) Antigone, in which the parallels between occupied and occupiers were not indiscernible; or of the contemporary Chinese film-maker Yimou Zhang (House of Flying Daggers (2004), etc) whose films are accepted as orthodox in China despite their underlying controversial message that the individual cannot win against the state. Inès is offerred several ways out of the situation. She speaks at length with an initially not unsympathetic though ill King. The councillors have a bland and unsubtle policy agenda in which logically, if the strategic ends of Portugal are predicated on the marriage of Pedro and the Infante, then either he must marry her by choice (which he will not and cannot), after an annulation of the marriage by the (uncooperative) Pope, or he must marry her by compulsion following the murder of Inès, who in exile would otherwise form a rallying point for anti-Portuguese dissent. When it becomes clear that the Infante is having non of it, packing her bags and heading home, it would seem that the King's persistence is more from boredom with the situation as much as anything else. And he says as much in Acte III Scène IV:

- Oh! Je suis fatigué de cette situation. Je voudrais qu'elle prît une autre forme....et je suis fatigué de vous, de votre existence. Fatigué de vous vouloir du bien, fatigué de vouloir vous sauver. Ah! Pourquoi existez-vous?

The king, delineates his raisons ignobles, and returns time and again to the very tedium of trying to sort out and save the situation from the vying suggestions and predilections, policies and prejudices of the court, which seem to make the action of these characters wallow in a glue or treacle that creates the slow-motion dreamscape of failing to running away from a pursuing fast overtaking terror. It is tiredness and indifference which take Inès to her death rather than political ambition, intrigue, vengeance or jealousy. The banality of the decision to kill her. The grinding boredom of have to finish her off. Get it over and done with. It is this which has contemporary resonance with some of our contemporary concern with disappearing people (i.e. the verb 'to disappear' a person, by contrast with a person who becomes invisible) and rendition. Inès has done nothing which the King can find deserving of punishment at all. When he hears of the situation, he says that Inès should be free, that the situation can be resolved. But as it grinds on, the King merely becomes bred with the inconvenient Inès who is, in modern terminology, disappeared. Pedro, obviously reappears her, as sometime we some of our national citizens reappearing, mainly in the press, recounting their treatment at the hands of the American in Guantanamo. They at least are not actual cadavers. In fiction, Orwell's Winston Smith returns from his interrogation changed, and in Stalinist Russia, some victims survived in 'retirement' in Dachas where though alive, they could do no harm, or lingered like a Speer and a Hess in Spandau long after their self-deemed peaks had passed ignobly into the past. Inès returns, but without victory and without celebration, and though crowned and accounted a queen of Portugal, this is surely one of the the most hollow of victories.

There was an English translation of this, but after reading the original text, my temptation to dabble with the translator's art is low-to-middling at best. Non existent wouldn't be far from the truth. Nonetheless, if the banality of evil is your thing (and clearly from the number of films and books about the Nazis, the Bulger killing etc etc is anything to go by), then La Reine Morte should excite and titillate. Presumably, it is available from abebooks.

Labels:

disappear,

Drama,

French,

Henri de Montherlant,

Hess,

James MacMillan,

Luís de Camões,

Opera,

Os Lusíadas,

Reine Morte,

rendition,

Scott,

Shakespeare,

Speer,

Yimou Zang

Thursday 1 April 2010

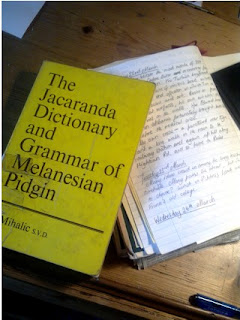

Fr. F. Mihalic SVD (1971): "The Jacaranda Dictionary and Grammar of Melnesian Pidgin."

Tok Pisin: the lingua franca of Papua New Guinea, and a language in its own right. Even if you don't speak it, and will never meet a Papua New Guinean in your life (shame on you) this book beats the average Teach Yourself French hands down. This is interesting even if you never leave England. Hell, this is essential reading even if you never leave your drawing room and a maid brings you tea on a tray and carries you to a commode in the corner of the room when you've overdosed on port. There are people, who choose this way of life. I kid you not. Here I am not speaking of anyone unfortunate enough through no fault of their own, through age or infirmity, to be confined to their own study walls. Here I speak of those who shall rename nameless, such as the currently practising London barrister who managed to contract teenage gout. Numquam poetor nisi podager (Ennius). Tennyson would have been proud of teenage gout.

My point is. If you can obtain a copy of this book, and if you have an interest in languages, then Fr. Mihalic has produced for you a readable, practical glory. If you ARE in fact heading for PNG, then you MUST read it, if only for the adversative mood form of the verb: Yu no kilim; paitim nating ("Don't kill it; merely hit it") etc. etc., and so on. "God i no gat pinis bilong en" does not translate in the way one might expect (it means "God is Eternal," rather than "God has no gentleman's whotsit"). As I say. Essential reading if you're travelling that way. Don't bother with the Lonely Planet by the way. In my experience, the speed at which things change in PNG, it is better to have a good grasp of the language skills than a map of a town which was burned to the ground three years ago since the glossy pic was taken. Your choice of course.

Some choice and eternal phrases from the poetical Tok Pisisn from Fr. Mihalic

Mi gat pispis blut - I have blackwater fever.

Pilai nating - to play for fun, to play soccer with little or no attention to the rules of the game.

Sindaun bilong ol i gutpela - They are leading good lives.

Em tasol i paitim mi - This one hit me.

Mi lukim wanpela pukpuk - I saw a crocodile.

All of these are far more useful than being able to ask the way to the coffee shop (there won't be one), the post office (its just been raided and burned down) or the police station (its no good going to them, they're the one ones who did it).

This title from the Jacaranda Press is probably best obtained in UK from AbeBooks.co.uk who have access to booksellers in Australia where most copies of this book exist.

Labels:

Languages,

Mihalic,

Non-Fiction,

Papua New Guinea,

Tok Pisin,

Travel

John Buchan (1930): "The Four Adventures of Richard Hannay"

Containing his four Richard Hannay books: The Thirty Nine Steps, Greenmantle, Mr. Standfast and The Three Hostages, this omnibus has appeal to any late-maturing former fans of Biggles. I'd love to feel too serious and grown up to still be enjoying these roaring tales of colonial era adventures, but then when I look about me on the train each day and see that the other passengers are either (1) playing games on their phones, (2) reading Harry Potter, or (3) reading "Passion" or similar tales of sassy London business girls struggling to balance spending their vast bonuses on frippery with finding lasting commitment from similarly shallow accountants and bankers, then I feel less bad about reading Buchan.

A cold rainy day when the masses are commuting back and forth, engaged in honest toil and tilling the earth outside, in offices or on trains. Bless 'em. That's a good day to spend some time warming the pot, getting down the favourite Spode cup and s., and settling back into some Richard Hannay. With the best will in the world, end as much as a fan of Capt. W. E. Johns as I am, the Thirty Nine Steps is quite poor. It would require being snowbound in a tent on Cader Idris, happily to be able to accept some of the coincidental meetings on moorland that Hannay experiences. I have been on many walking trips in Britain and overseas, on moors and mountains but I have yet to meet in quick succession: a member of parliament, two of the chaps from prep school, a kindly blacksmith, a hook nosed pirate with a surprising weakness for toffees. Individually yes, of course. On seperate trips, yes. But one after the other within five hours of leaving Kinshasa on foot. Never. Assuming you can come to terms with the outrageous levels of convenient meetings, and some of the more colonial expressions used, then the Thirty Nine Steps is for you. Mind you, it only took a few hours to read, so assuming you are on a train, have forgotten your adult-covered Harry Potter (so everyone else assumes you're reading Thucydides presumably) and you're not requiring more entertainment than, say Birmingham New Street to York, then this is for you. If you're off to Papua New Guinea for three months, this will not fit the bill. You'll have finished all four books before you're being strip searched by Australians in Sydney airport, let alone hanging out with the wontoks on the Highlands highway.

On real adventures, always take books dealing with the mundane or the pastoral. Take my word for this. Little Dorrit is what you want to be reading when the fourteen year olds outside your hut with the automatic weapons are keeping you awake on the wrong side of the Sepik. That said, I'm enjoying Greenmantle.

At home, on a rainy day in Oxfordshire, make do with John Buchan.

Bookshop Guides

AbeBooks and Amazon have opened up a world of book acquisition to me, in particular, I am able to find things online which I have always wanted, or which I find referenced in footnotes, text or conversations. If I know what book I'm currently seeking, and it has nosed its way to the top of my next tp read list, then 9 times out of 10, online is the place to get it. But what about the authors I haven't yet heard of, the titles which have slipped through the net, the less popular (and often therefore, more interesting) editions, or even field of interest which I would just not otherwise stumble across. The serendipitous picking of a book from shelves because it happens to be near the space which would have contained (had the bookshop had it in stock) the book I went there to seek. The divinatory practices of stichiomancy and bibliomancy involve running a finger over a page of text at a randomly opened page in a sacred volume of some description. Where the finger stops, the sentence or paragraph is interpreted in the light of the question being asked.

Attic Books

Attic Books

14 St James Street

Cheltenham, GLOS, United Kingdom GL52 2SH

Tel: 01242 255300

WEBSITE

Books and Ink Bookshop

4 White Lion Walk, Banbury, Oxon OX16 5UD

Tel. (01295) 709769

Email: books@booksandink.co.uk

WEBSITE

How about running your hands along a bookshelf and pulling out books at near random. Ignore for the moment the dubious process of divining the future or answering life's questions (most of which would be best served by finding a sentence which says:"Have you thought of pulling your finger out? Get a grip!"). Instead, take your chosen text of interest, or as I said, the place where it would have been on the shelf had it been available. Scan round the area at random, pull out books that look good, nicely bound, familiar publisher, nice typeface, whatever. Skim read them. Most books can be skimmed in about 20 seconds. Accept or reject provisionally. Enter the bookshop knowing you will spend a nominal sum there irrespective of whether they have you exact book or not. AbeBooks can't give you this random chance element. Walk through the bookshop, scan shelves you wouldn't normally go near. Talk to the owner. Some bookshops have a good feel. On every shelf there is about 20% of the contents which I already own, want to own, or will actively try to acquire. Some bookshops have nothing. Nothing at all. I just get a dead feeling that I really don't want anything they have. These two extremes are odd, and probably just reflect my interests, financial state or bookshelf space at the time rather than a quantitative measure of the worth of the bookshop. Anyway, try it.

The Inprint Bookshop in Stroud has a useful listing of second-hand bookshops in UK with a summary of each. The links, below, to the bookshops of Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire comprise our 'local' stomping grounds.

I will vaguely try to enlarge my bookshop going habits and review one or two new shops online as I use them. I'll put links to the bookshops on the Blog sidebar. There is a better online secondhand bookshop guide HERE, with the opportunity to submit your own comments on bookshops you have visited.

From Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, there are three which immediately spring to mind as always being worth a visit or detour.

- Attic Books in Cheltenham: Roger, who owns and runs it, is an excellent character, looking oddly like Gandalf or Dumbledore, his micro-bookshop on St. James's Street (next to a car park which always has parking) has a wealth of buyable volumes. He has good military history, novels, natural history, biography and poetry section (and much more). His prices are knowingly more than generous and I usually have to haggle the prices up a little to feel that his kindness isn't going to put him out of business. I have no idea if anyone else does this? It isn't that he doesn't know what he is selling, or how much it is worth, it is just that his nature ill-suits him to selling things to the public. Become a regular here! English eccentricity at its least commercial best. If only he'd have a pot of coffee on in the upstairs room, I'd pay to just sit in here and talk, never mind actually buying books. Roger obtained the moderately hard to find three volume Kilvert for me in the pre-AbeBooks days, and a Sydney Jary 18 Platoon which is strangely out of print despite its definitive account of the battle for France which was the staple reading for cadets at Sandhurst. Online catalogue HERE, but really, GO there. Persuade him to get the coffee machine.

- Books and Ink Bookshop, Banbury: To paraphrase Saki (Reginald on Christmas Presents: "People may say what they like about the decay of Christianity, the religious system that produced Green Chartreuse can never really die"), so long as this book shop remains open, Banbury town centre will not entirely be lost. We can just about maintain life and soul in Banbury so long as Books and Ink remains open. The shelves here are full of good things. The prices are very good. I don't have any figures for the literacy rate of this town, and I wouldn't like to cast any aspersions, but either the owner has a preternaturally fine taste in re-stocking the shelves and works at it like a demon, or the masses aren't surging in here to take these goodies off his hands at the rate that this bookshop deserves. Again, like Attic books in Cheltenham, I do strongly recommend that you shop here. Keep this bookshop afloat, otherwise Banbury is on the list for being ploughed back to earth and the ground salted. If you could persuade the owners that a coffee machine and plate of cakes would fit into a corner, then so much the better.

Attic Books

Attic Books14 St James Street

Cheltenham, GLOS, United Kingdom GL52 2SH

Tel: 01242 255300

WEBSITE

Books and Ink Bookshop

4 White Lion Walk, Banbury, Oxon OX16 5UD

Tel. (01295) 709769

Email: books@booksandink.co.uk

WEBSITE

Wednesday 31 March 2010

John Ruskin (1857): 'The Elements of Drawing'

"I do not think it advisable to engage a child in any but the most voluntary practice of art."

Ruskin's preface to this self-study guide to drawing, exhorts parents and readers on a general approach to art which is as different from a modern Learn to Paint book as Wordsworth's Guide to the Lakes is different from a Lonely Planet Guide. The modern art book lists essential primary colours of the medium and recommends basic appropriate paper types. Compare to Ruskin in his preface: "If a child has many toys he will merely dawdle and scrawl over them; it is by the limitation of the number of his possessions that his pleasure is perfected and his attention concentrated." He is as insistent on the background preconditions to approaching the practice of art and Wordsworth is that we approach the Lakes along a certain valley at a certain time of the day. No-one but a fool would stand at Innominate Tarn at any time of the day but late afternoon!

Labels:

Art,

Artists,

Non-Fiction,

Ruskin,

Wordsworth

Monday 29 March 2010

David A. Cross (2007): "Cumbrian Brothers" Fell Foot Press

This is the latest slender edition from Fell Foot Press, and the most recent publication from independent art historian David Cross. Like his previous work, A Striking Likeness, which considers George Romney's 18th Century portraiture, the subject of this book is a Cumbrian Artist. In Cumbrian Brothers, Cross introduces us to the illustrated letters of lakeland artist Percy Kelly to the poet, Norman Nicholson. The introduction is all we need to set the scene for the pictures and letters, beautifully reproduced, which comprise the bulk of this text.

Neither the writer nor the painter would otherwise have been on the tip of my tongue without this book, which provides a sufficiently concise but compelling introduction to encourage me to undertake a little more reading in the area. I'll probably spend a little time in later posts to discuss what I'm learning here about poets and artists in general, and these two specimens in particular.

To my shame, some of the more outrageously self indulgent uttering of the poet in his letters are not beyond the kind of thing I find myself saying (hopefully only in the hearing of the cats, who are above such pettiness.) This was a useful heads-up to the possible nature of my own wanderings in art and literature. A warning to us all, but also an encouragement to find our own meanings in the medium of expression which we choose for ourselves and take for our own. I shall take this as the starting point for further reading around the subject of art and writing in general. Next on the list, and not too far down the pile on the study floor, might be another mildly obscure book from the British Museum Press: Kim Sloan's: A Noble Art: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters c.1600 - 1800.

T.C. Lethbridge (1980): "The Essential T.C. Lethbridge". T. Graves & J. Hoult (eds.)

I came to this volume via one of its editors, Tom Graves, who wrote a short book, Pendulum Dowsing (1989) which references the work of Lethbridge. Lethbridge was a Cambridge University archaeologist who worked for many years within the accepted tradition of his discipline. Gradually, from his archaeological work on "the confused and difficult subject of the ancient Gods in Britain", to a personal investigation which takes a turn from the conventional as Lethbridge takes up pendulum dowsing.

This produced the same feeling of genuine scholarship applied to a less conventional area of study as reading, say T. J. Hudson's (1893) Psychic Phenomenon, which I picked up randomly for its attractive binding out of a cardboard box many years ago for £1- in a student union book sale. I remember enjoying Hudson at the time, and then recommending it and lending it to another student who disappeared from the scene never to be seen again. These were the times before Amazon or AbeBooks.co.uk, so it was not until much later that Psychic Phenomenon could be tracked down again, it not being terribly or outrageously well read these days. I always remember the books I lend, and to whom, and if I have received them back again. Likewise I know which on my shelves aren't mine, but borrowed and a sense of obligation to return them lingers almost palpably about the shelf on which they sit. Hudson went into that category of Lost Books, a file in my mind which is not so full now as it used to be, of those lent volumes which are irredeemably lent to the irredeemable. From a more recent re-read of his Victorian works, I came to Graves, then Lethbridge and other minor madnesses such as Rupert Sheldrake and The Sense of Being Stared At (2003) or 1782 French grimoire, Le Petit Albert - this latter which it would be wrong to commend in any way at all.

Lethbridge reminds us of the interconnectedness of things:

I have enjoyed one great advantage over many of my contemporaries. It has never been necessary for me to stick closely to one line of study, and thus work it to death. There has always been time enough to gain at least a passing acquaintance with subjects other than archaeology... Although this may well have led to my becoming a "jack of all trades and master of none", it has nevertheless provided me with a great store of experience, with some of which I at times bore my friends.

(p. xviii)

This broad-based interest in inter-connectedness of areas of intellectual endeavour very much represents what this Blog is trying to achieve with regard to winding the personal serendipitous highways and by-ways of books, old and new. The conceptual leads taking us from one book to another, and helping to explain the unconventional homes of certain books next to others on the shelves of the home library.

Roger Deakin (2007): "Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees"

Having recently been given and immediately devoured whole a copy of his 1999 book, Waterlog, I have just obtained Deakin's 2007 sequel like volume, Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, which I intend full to savour. A third book, Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, came out in 2008 and similarly to Wildwood, it too was published posthumously after his sad death in 2006.

This highlights a theme I have always been interested in: books which will not not be written. What would Alain-Fournier have produced to follow Le Grande Meaulnes had he not died on the Western Front, or Saki whose Reginald stories of high Edwardian satire evolved (The Square Egg and other Tales, etc.) in the light of the author's period in the trenches (where he died, his last words being quoted somewhere as: "Put that bloody cigarette out!")? Would Hillary have written something to compare with his only book, The Last Enemy, and could Saint-Exupery (Le Petit Prince) have gone back to writing had he not disappeared over the Med? Wildwood may turn out to fit into a "died too young" theme, which in turn may overlap for obvious reasons with a category of military autobiographical accounts, of which I am also rather fond (e.g. Sydney Jary's essential reading: 18 Platoon or anything by Milligoon).

Sunday 28 March 2010

Foucault, M. (1961): Madness and Civilization

Someone was staring to read Folie et deraison: Histoire de la folie a l'age classique, so I am quite happy to start a thread on what the current Routeledge version claims to be "the most influential, and controversial text in this field during the last forty years." Having read and re-read the first three chapters several times without ever having got any further, this is a good opportunity to start over from my almost blunted purpose.

A Wikipedia summary to get you going. How does the impression on your mind of the summarised version differ from the experience of a reading of the original text, and do we in fact benefit from the time spent in reading this, as opposed to just Googling the summary and going for a run instead?

Labels:

Foucault,

Madness and Civilization,

Non-Fiction,

Routledge

"Crime and Custom in Savage Society" By Bronislaw Malinowski (1926)

Any takers for this classic text? Available free online HERE for those who don't already have it on their shelves. Shame on you. I'm working from the 1966 8th edition which has been withdrawn from UCS Sociology Dept at some point in the distant past and retailed to me through abebooks.co.uk, of which you are no doubt already aware. Seventeen chapters in two parts beginning with "The Automatic Submission to Custom and the Real Problem", and ending with "The Factors of Social Cohesion in a Primitive Tribe." Remembering that this was first published in 1922 and take into account that one of the reasons for starting with the older books before the more recent descendants, so to speak, it gives us a chance to look at the ideas in their embryonic but fully contextualised form rather than the gloss or digest of what Malinowski is said to have said passed down as footnotes of footnotes. Part of the point in starting here is to get an idea of the original text, and from it to form a set of potential trajectories. Where could these ideas have led to when they were written in 1922? Not only where did they they lead, but what could they have led to. Reading references to older texts in more recent books, particularly in some recent scholarship, it is possible for the reader, and likewise the reader of history texts, to get the idea that the development of thought from then to now was a linear and predictable process. Clearly this view should at the very least be questioned. So I would propose that it is preferable to read and react to the original text, bearing in mind when and for whom it was written, what it was trying to convey to which audience. We should choose rather to re-read the original in preference to a quick Google search for Wiki-commentaries in order that we might begin to build a substantial base of knowledge on which those later refinements and commentaries can more fairly sit. Presuming, that is that we are reading for pleasure and expanded self-knowledge, rather than hoping to pass exams in the immediate future or knock out a quick cut'n'paste essay.

Labels:

Crime,

Custom,

Malinowski,

Non-Fiction,

Routledge,

Savage Society

Walter Lippmann (1922) "Public Opinion"

"Written by one of the most influential men of his times and one of the greatest journalists in history" it says on the blub. I'm a fan, but have to say that I haven't re-read it for some years. Just getting into it again now and I thought this would be a good chance to see if the blog format works in any way. Just skimming the text over in a few minutes, I saw that some of the things Lippmann says are the ultimate source of some of the things I seem to find myself spouting about regarding the actions of the press. How current is he? What is he actually saying? Is it still relevant?

What has Lippmann to say in 1922 which I can still use to help me understand what I read and hear in the press at the moment? Is presumably my starting point.

Labels:

Free Press,

Non-Fiction,

Public Opinion,

Walter Lippmann

Something in the Woods - Rosie Fairfax-Cholmeley

As one Luddite to another, I have no idea how to adopt all the features of this online book reading scheme into my otherwise non-web-based daily habits. nonetheless, I'll share authoring of these pages will all and sundry who are interested, and who knows, we may be among the first to actually use the internet for something other than cutting and pasting other peoples' crap into essays or watching images which would not be available in anything published by OUP.

Banbury Book Club Blog

Presuming that you aren't a bored housewife of Banbury wishing to gossip about what you saw the neighbours doing through your net curtains with their hosepipe, or wishing to rant on about bonfires and how little Jimmy gets asthma if anyone so much as burns a hedge clipping, then this may be for you. James, Hannah, Rosie and Robin - suggest titles, add comments or questions, cut and paste text, bibliographies...whatever.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)